On Wednesday the 4th of April

2018 I took a trip over to Nottingham to attend the lecture hosted by the

Nottingham Empyrean Pagan Interest Group. These often informal presentations,

are held at the Theosophical Hall on Maid Marion Way, which is itself a main

thoroughfare on the edge of the city centre.

Mrs Keith's presentation

covered five primary points which she conveniently presented as part of her

introduction.

1. Magic is a universal phenomenon

2. Less hard evidence the further back in time we go

3. The Germanic and Anglo-Saxon Systems

4. Leech Books of the early Medieval Period

5. The blending or overlap of Pagan themes hidden under a

veneer of Christian belief.

Mrs Keith began with a run

through of the aforementioned universal phenomenon, briefly mentioning the

release of land from curses and the significance of particular numbers, for

example three and nine. Continuing the theme our attention was drawn to

Christian Prayers incorporating Pagan elements, such as invocations of the

Goddess Erce.

Moving on we were taken on a

journey through the Leechbooks of the Saxon Period, noting that although

incorrect to refer to practitioners as shamans, the methodology could in some

circumstances, be described as similar. The conjoining of Pagan and Christian

magic of this early period is noted to have continued well into the twelfth

century. The Saxons however, placed a considerable emphasis upon dreams. This included

various omens, acts of divination and charms to protect individuals from the

Night Goblin. One very interesting charm required the offering of seven

communion wafers.

As one would expect when

looking at the late Anglo-Saxon period and the increased contact with

continental Europe. There is an increasingly central and southern European

influence upon the sorcery of the period. Scandinavia arts in the form of Galdr,

meet the seven sleepers of Ephesus (a Christian story) and once again, charms

invoking Erce. All of which merely serves to illustrate how rich were the

magical traditions of the Saxon Period.

Throwing bridleropes,

spiderwights, goblins and wyrms into an already heady mixture, Mrs Keith

introduced charms to protect from poisons and venoms. These included the well

known ABRACADABRA charm but also many lesser know arts, such as the Lay of the

Nine Werts or Worts, the Nine Twigs of Woden, also known as the Glory Twigs and

the Adder's nine venoms. My head was beginning to spin at this point.

Obviously when looking at the

sorcery of this period it is important to understand the importance of herbal

charms and much of what has already been mentioned, are charms of that nature.

Mugwort, perhaps the oldest known wort, is perhaps of pre-eminence amongst

them.

In an age when medicine in

any modern sense was unknown, it was the street magicians and leechworkers to

whom the community would turn. Here seeking comfort and protection from a

varity of ailments, including the toothache so often associated the wyrm, we

note that 'wyrms' are always harmful, malicious and blamed for all manner of

malady. Sometimes an illness was 'charmed' into another object, such as a stone

or tree, while at other times a physical talisman such as a holed stone was

required as an amulet.

With the coming of

Christianity the shift in perception towards what was previously regarded as

positive changed. A denigration of the Elves, the Aesir and Mightwomen began

and rather than asking for blessings, in fear people began to seek protection.

This was even to manifest in a form of European smudging using 'Elfhorn' to

banish elves from the home environment.

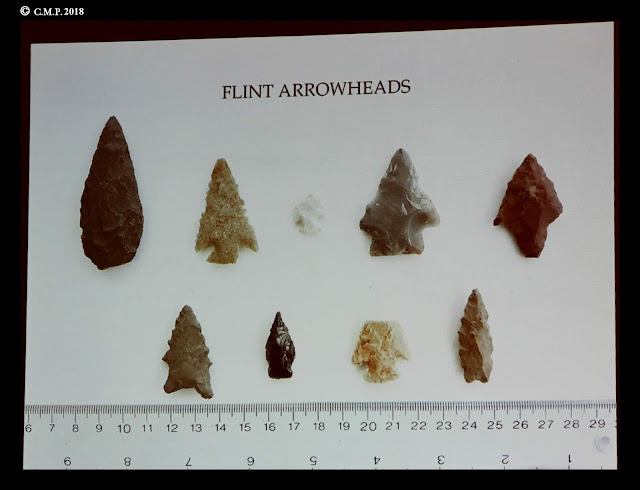

One cannot mention the Bright

Ones in relation to Anglo-Saxon magic without there being some mention of Elf

Shot and it is worth mentioning at this point, that amongst the many physical

exhibits on display. Mrs Keith was able to produce some fine exhibits to

illustrate the lecture.

Elf shot itself had of course

a variety of uses and was itself greatly feared. A charm against 'sticking' or

severe pain, and mentioned in poetry, we find the word shot used in conjunction

at various times. Aesir Shot, Elf Shot and even Hag Shot all apparently

referring to a knife charm involving a potion of fever few.

Jumping ahead to the

seventeeth century, we find that the beliefs and practices of the pre-Conquest

period had survived in folklore amongst the common people; even if forgotten by

the elite. Elf Shot is documented in the trial records of Isobel Gowdie for

example. Here they are the feared arrow heads flicked on a thumb nail and believed

manufactured by the Devil himself! By this time however, the use of the

arrowheads has developed, now both a tool of malefic sorcery and conversely,

mounted as a amulet to project the bearer from the Elves. Other methods of

protection included the Elf furrow, a form of curved ploughing used to confuse

the 'little people' and protect the crop.

Returning to our pre-Conquest

period we were introduced to the Wurtgalster, a feminine noun meaning

plantcharmer. Both interstingly and amusingly, we were informed that the Church

had punishments for women if their magic worked. I reiterate with amusement

that it was only if the magic worked!

Tying all of this together to

bring our journey to an end, we were guided through the use of brambles in

healing, before being brought up the fifteenth century to examine childbirth

charms. The various influences of the pre-conquest period being aptly shown as

near prescient, in that their survival in our modern world can been illustrated

by the many grave goods and symbols of the period. Anglo-Saxon magic has not

passed away, it survives today in our folklore and our memory.

Nottingham Empyrean Pagan

Interest Group

An excellent review of a very interesting and well delivered talk, thanks for writing it up..

ReplyDelete